Fort Monroe planners are still trying to decide whether a trolley or water taxi can be used to help visitors get around the property.

By Robert Brauchle, rbrauchle@dailypress.com | 757-247-2827

December 26, 2012

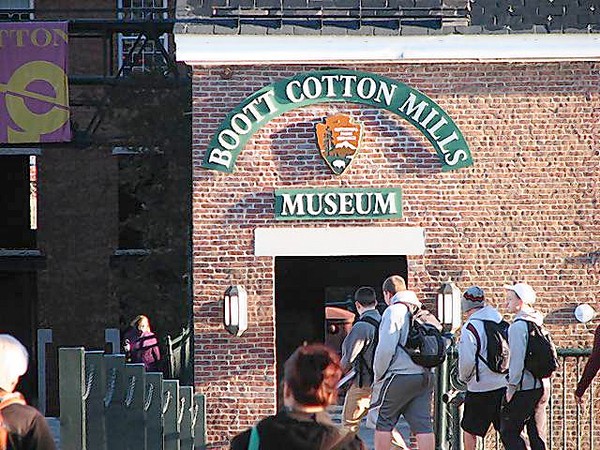

The Lowell Historic National Monument visitors center sits on a busy downtown street. The visitors center includes displays and a movie theater explaining Lowell’s past.

Students from nearby apartments walk past the National Park Service museum in downtown Lowell, Mass.

LOWELL, MASS. — In the mid-1800s, a seemingly endless stream of Southern cotton was shipped to booming New England cities where the raw material was woven into printed cloth.

The clang and racket familiar to 19th century textile factories is still heard here in the ground floor of the National Park Service’s Boott Cotton Mills Museum

Guided tours of this operating weave room — earplugs are included — are among the interactive exhibits about the rise and fall of industry here.

Once visitors leave the museum, they can hop on a nearby electric trolley that carries them along in 19th century style. With their wicker seats and hand-crank controls, the cars plod along the tracks, powered by electric cables overhead, stopping at select historic sites downtown.

Wandering past quaint mom-and-pop shops and repurposed mill buildings settled next to museums and historic sites, it isn’t always apparent where Lowell National Historical Park begins and where it ends.

That feel is something officials at Fort Monroe hope to emulate.

“Our goal is to work closely so people don’t think about the intricacies of whether they’re on park service land or commonwealth land,” said Fort Monroe National Monument Superintendent Kirsten Talken-Spaulding.

Preserving history

Several factors beyond the park service rangers in their green and gray uniforms protect the historic qualities of both Fort Monroe and Lowell National Historical Park.

More than 100 acres of downtown Lowell’s man-made canal system and large mill buildings are listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Being included on the register means Lowell must ensure that any development within the district’s boundaries is consistent with the 19th-century setting the city wants to preserve, said Lowell Planning and Development Director Adam Baacke.

Any significant project within that area must be approved by the Lowell Historic Board before it reaches city planners and the City Council.

“The business community and city leadership have really embraced historic preservation,” said Peter Aucella, assistant superintendent for Lowell National Historic Park. “All of these things didn’t come together by accident.”

At Fort Monroe, the entire 565-acre property is listed on the historic register, even though only 325 acres are within the national monument created in 2011.

While the national monument proclamation comes with the glitz and glamour of the park service presence, the historic register listing provides the teeth to preserve Fort Monroe’s history.

A historic preservation officer will review proposed projects to make sure they comply with the property’s design standards, which are detailed in a two-volume, 633-page manual available on the Fort Monroe Authority’s website.

The standards, the document says, “shall be applied to all undertakings at Fort Monroe, including building rehabilitation, new construction, maintenance, or any activity that has the potential to affect historic resources directly or indirectly.”

Harnessing development

Using the park service sites and public financing incentives as carrots, the city of Lowell has enticed private developers to repurpose the city’s historic mill building buildings, once thought to be relics of the city’s industrial past.

It’s taken close to 40 years, but the economy in downtown Lowell is flourishing, city officials said.

Copyright © 2012, Newport News, Va., Daily Press

dailypress.com/news/hampton/dp-nws-fort-monroe-transformed-military-bases-20121227,0,2796065.story